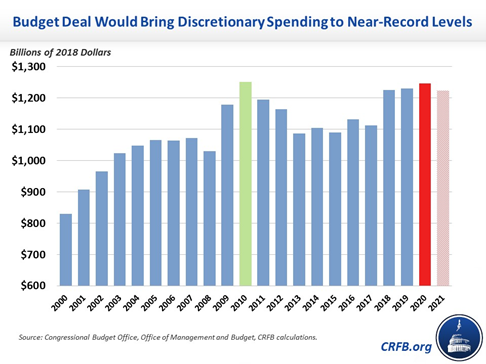

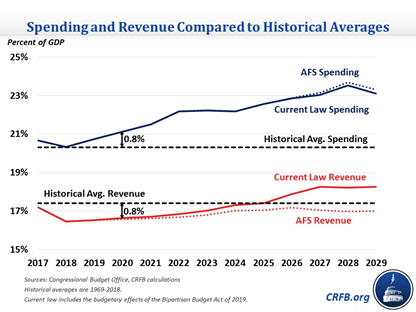

The Government Contracting Industry is a complex marketplace. No other industry is as dependent on the successes and failures of Federal policy, regulation, and Congressional leadership. Our ecosystem lives or dies by it. Elements of the sector ebb and flow depending not only on the needs wants, whims, and votes of American citizens but also the global stage, all of which command our ~$1T competitive landscape pipelined through Federal discretionary spending.

Vendors enter into the fray with dollar signs in their eyes, and at a glance, they’re right to be excited about the potential. But those of us in-the-know understand working with the Federal Government isn’t an opportunity to print money, and what is considered a steady investment still has its ups and downs.

While the World sets its sights on 2021, The Pulse decided to take a step back and examine the state of Federal discretionary spending (procurements and grants) over the last ten (10)…yes 10… years, as we close out the decade not with a whisper – but with a boom.