Article Category: Federal Agencies 101

-

USACE 101: What Vendors Should Know About the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

USACE 101

What Vendors Should Know About the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) has a remarkable history as a vital federal agency for over 200 years, beginning in 1802 with a dedicated group of military engineers focused on building coastal fortifications. Over the years, USACE has transformed into a major global organization, its mission now encompassing military readiness, infrastructure development, environmental stewardship, and disaster response.

Agency Overview

The Basics.

Congress established USACE on March 16, 1802, primarily to support military engineering and fortification needs, focusing initially on building coastal defenses and essential infrastructure for national defense. Over the last two centuries, however, USACE has evolved significantly, broadening its mission and capabilities far beyond its military origins.

In the 19th century, ‘the Corps’ began to engage more actively with civil infrastructure, collaborating closely with civilian communities. It was pivotal in constructing iconic national landmarks, such as the Washington Monument, completed in 1884, and managing critical waterway projects essential for commerce and transportation. During this period, USACE earned recognition for its water management and civil engineering expertise, setting the stage for its future growth. The early 20th century marked a time of profound change, highlighted by the construction of the Panama Canal from 1904 to 1914. USACE was instrumental in overseeing this ambitious project, showcasing American engineering on a global scale.

In the aftermath of the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, the Corps took on new responsibilities related to flood control and disaster response. This led Congress to pass the Flood Control Act of 1928, which designated USACE as the primary federal agency for flood mitigation. World War II (1939-1945) transformed USACE further, as the Corps rapidly constructed vital military installations, airfields, ports, and other facilities, demonstrating its ability to deploy infrastructure swiftly.

After the war, USACE helped rebuild regions affected by the conflict, solidifying its international presence and expertise in complex construction and logistics. In the latter half of the 20th century, USACE expanded its repertoire by undertaking major civil engineering projects, including dams, reservoirs, navigation locks, levees, and hydroelectric power facilities. Legislation such as the Clean Water Act of 1972 and the Water Resources Development Acts beginning in 1974 broadened the Corps’ focus, requiring a balance between infrastructure development and environmental protection.

Fast-forward to the catastrophic impact of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, which exposed glaring weaknesses in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ emergency response capabilities. The devastation wrought by the storm highlighted the urgent need for comprehensive reforms in risk management, fostering robust community coordination, enhancing disaster response strategies, and strengthening infrastructure resilience. In the years since, the Corps has confronted various emerging challenges, including escalating cybersecurity threats, the far-reaching effects of climate change, and the pressing imperative for sustainable energy solutions.

Spending Trends (FY19 – FY23)

Place of Performance (Top States)

- Texas (5%)

- Florida (4%)

- California, Arizona, and Virginia (3% each)

Industry Codes (Top NAICS)

- 236220 – Commercial & Institutional Building Construction: $42.7B

- 237990 – Heavy/Civil Engineering Construction: $27.2B

- 237310 – Highway/Street/Bridge Construction: $11.8B

- 541330 – Engineering Services: $9.5B

- 562910 – Environmental Remediation: $5.6B

Industry Codes (Top NAICS)

- Y1JZ – Miscellaneous Buildings Construction: $14.1B

- Y1PZ – Other Non-Building Facilities: $7.7B

- Y1LB – Roads/Bridges: $7.5B

- Y1KA – Dams: $4.3B

- C219 – A/E General: Other: $4.1B

Acquisition Pathway (Top Vehicles)

- GSA MAS: $2.1B

- Rapid Disaster Infrastructure (RDI) MATOC: $1.7B

- USACE and DHS CBP Horizontal Construction (East/West): $1.9B combined

- Utility Monitoring and Control Systems (UMCS IV & V): $1.2B combined

- Operations and Maintenance Engineering Enhancement (OMEE): $667M

Structure and Organization

A Global Mission with Military at Its Core.

For federal contractors, USACE is a vital engine behind the military’s global infrastructure. Under the current leadership of Lieutenant General William H. “Butch” Graham Jr., the 56th Chief of Engineers, and General Kimberly A. Colloton, the Deputy Commanding General and Deputy Chief of Engineers, the Corps continues to expand its initiatives in engineering, environmental stewardship, and technology.

Today USACE supports hundreds of military installations worldwide, including direct mission support at 42 Army installations, 13 Air Force bases, and 16 Department of Defense and host-nation partner installations—just within the North Atlantic Division alone. USACE also maintains a presence in over 130 countries, delivering critical services that support U.S. defense and security goals globally.

This unmatched scope positions USACE as a premier federal customer and partner for companies specializing in construction, environmental remediation, cybersecurity, energy performance, and advanced infrastructure systems.

A Deep Bench of Specialized Capability.

USACE’s capabilities are further extended through a network of Centers of Expertise, which federal contractors should understand when aligning their services with agency priorities. These centers fall into two categories: Mandatory Centers of Expertise (MCXs) and Technical Centers of Expertise (TCXs). Each of these centers ensures quality, consistency, and cutting-edge expertise across USACE’s projects while creating entry points for contractors with relevant capabilities to engage deeply with the Corps’ specialized missions.

Mandatory Centers of Expertise

There are 14 MCXs across the Corps, designated by USACE Headquarters for their unique, critical technical capabilities. As of 2025, notable MCXs include:

- Missile Defense: Located at the Huntsville Center, this MCX supports missile defense programs and has announced upcoming contracts and conferences related to its mission

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. - Protective Design Center: Established in 1986, the PDMCX focuses on antiterrorism and force protection, providing expertise in protective design.

- Environmental and Munitions: Provides expertise in environmental remediation and munitions response.

- Dam Safety Modification: Located within the Huntington District, this MCX focuses on dam safety modifications.

- Hydroelectric Design Center: Based in the Portland District, it serves as the MCX for hydroelectric power economic evaluation, engineering, and design.

- Modeling, Mapping, and Consequences Production Center: Located within the Vicksburg District, this center specializes in modeling and mapping for risk assessments

Technical Centers of Expertise

USACE operates 26 TCXs, which offer exceptional, specialized support but are not required for use. As of 2025, notable TCXs include:

- HVAC Technical Center of Expertise: Located at the Huntsville Center, this TCX provides expertise in heating, ventilation, air conditioning, and refrigerant systems. It was most recently re-certified by USACE on April 26, 2023 .

- Energy Savings and Performance Contracting/Third Party Financing: Offers expertise in energy efficiency and financing mechanisms for energy projects .

- DD Form 1391 Processor: Specializes in the preparation and validation of DD Forms 1391/3086 for military construction projects .

- Operations and Maintenance Engineering Enhancements: Provides support for operations and maintenance engineering improvements .

- Installation Support: Offers expertise in facilities reduction, repair and renewal, and centralized furnishings.

Mandatory Centers of Expertise

- Medical Facilities: Providing lifecycle support for medical and research facilities.

- Ballistic Missile Defense: Offering expertise in missile defense infrastructure.

- Electronic Security Systems: Specializing in the design and implementation of electronic security measures.

- Utility Monitoring and Control Systems: Focusing on the integration and management of utility systems.

- Facilities Explosives Safety: Ensuring safety in facilities handling explosives.

- Control Systems Cybersecurity: Addressing cybersecurity for industrial control systems.

- Military Munitions: Managing the lifecycle of military munitions.

- Ranges and Training Lands: Overseeing the development and maintenance of training facilities.

- Hydroelectric Design Center: Specializing in hydroelectric power plant design and evaluation.

- Inland Navigation Design Center: Providing expertise in navigation infrastructure.

- Marine Design Center: Focusing on naval architecture and marine engineering.

- Modeling, Mapping, and Consequences Production Center: Analyzing potential consequences of infrastructure failures.

- Protective Design Center: Designing facilities to resist various threats.

- Transportation Systems Center: Expertise in military airfields, roads, and railroads.

Technical Centers of Expertise

- Facility Systems Safety: Providing engineering and safety expertise in facility systems.

- HVAC: Offering technical support in HVAC systems.

- Installation Support: Supporting public works business processes and systems.

- Cybersecurity for Industrial Control Systems: Addressing cybersecurity challenges in control systems.

- Energy Savings Performance Contracting: Expertise in energy efficiency and financing mechanisms.

- DD Form 1391 Processor: Specializing in the preparation and validation of military construction project documentation.

- Hydrologic Engineering Center: Supporting water resources management responsibilities.

- Joint Airborne Lidar Bathymetry Center: Performing operations in airborne lidar bathymetry.

- Paint Technology Center: Providing expertise in paints and coatings.

- Photogrammetric Mapping: Offering rapid response photogrammetric mapping support.

- Power Reliability Enhancement Program: Enhancing power reliability across installations.

- Rapid Response: Providing time-sensitive project support during emergencies.

- Welding and Metallurgy: Expertise in welding and fabrication projects.

Contracting and Obligation Trends

Where the Dollars Are Going.

USACE plays a key role in federal contracting. Over the last ten years, it has awarded an average of $21B yearly. In FY23, USACE set a record by awarding $28.9B in contracts, showing its growing importance in national infrastructure and emergency response. Most of USACE’s spending goes to construction and engineering services. GSA’s Multiple Award Schedule (MAS) is the contract type USACE uses most often.

Helpful Hints

- USACE typically procures IT services, R&D, and ‘Specialty Contracting’ under NAICS 541512 and 541715.

- While the top “vendor” is technically the Federal Republic of Germany (due to host-nation agreements), SAIC, Lockheed Martin, Honeywell, Johnson Controls, and Siemens are top technical and building systems integration vendors.

Competition and Small Business Trends

- Roughly 90% of all USACE contract dollars were awarded competitively between FY19 and FY23—a strong indicator of open market access.

- While $5B per year goes to Small Disadvantaged Businesses (SDBs), only 38% of obligations were Small Business (SB) eligible, which is lower than the federal average, especially compared to agencies with more IT and services portfolios.

Grant Trends

Where the Dollars Are Going.

USACE is widely recognized for its significant federal construction contracts. However, in the past decade, it has made strides in grant-making, opening up valuable opportunities for academic institutions, nonprofits, and technical partners. Since FY17, USACE grant awards have steadily increased, peaking at an impressive $335M in FY19.

Despite this overall growth, annual grant funding can be quite variable, as it is influenced by shifting mission priorities, congressional directives, and various pilot initiatives. Notably, 98% of USACE grants are structured as cooperative agreements involving substantial government participation in project execution. In contrast, only 2% of these grants are traditional block or formula grants, highlighting the collaborative and mission-driven nature of most USACE awards.

Helpful Hints

- Notably, 17.5% of awards supported multi-state or nationwide efforts, often tied to research or conservation. Top places of performance are California (15%), Alaska (13%), Louisiana (4%), Colorado (4%), and Hawaii (4%).

Top Programs and Priorities

- Conservation and Natural Resource Rehabilitation on Military Installations: $397M

- Advanced Research in Science and Engineering: $345M

- Reimbursement of Technical Services (State MOAs): $158M

- Legacy Resource Management and Environmental Research: $65M+

- Youth Conservation, Fisheries, and Collaborative R&D: Smaller but mission-aligned awards

Future Investments and Commitments.

FY25 Standstill.

USACE stands at a critical crossroads in FY25. The most recent CR has froze funding at FY24 levels and blocked all new project starts unless explicitly authorized.

A CR doesn’t just delay progress—it undermines the Corps’ evolution into a forward-facing infrastructure agency. Projects that were shovel-ready in FY25 could sit idle for months or longer.

For USACE, this means:

- Delays to major ecosystem and infrastructure projects

- Missed award cycles for contractors

- Stalled planning horizons on multi-year programs

- Deferred progress for communities facing flood risk and climate vulnerability

Budget Planning vs. Administration Realities.

The current Administration has significantly influenced USACE’s operations and priorities, particularly through actions taken by the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) and the Department of Justice (DOJ) Environment and Natural Resources Division (ENRD).

Contract Cancellations and Operational Disruptions

While specific USACE contracts are not enumerated in public records, reports indicate that DOGE has targeted the agency for significant cuts. This includes the abrupt termination of leases for USACE district offices in Chicago, Charleston, and Jacksonville, disrupting regional operations and staff logistics.

Environmental Enforcement Rollbacks

Meanwhile, the ENRD—under Attorney General Pam Bondi—has dismantled core environmental justice efforts by terminating programs and sidelining attorneys with expertise in environmental law. These moves have paused litigation, weakened regulatory oversight, and cast doubt on the government’s commitment to environmental enforcement.

Impact on FY25 Strategy

These administrative actions have directly undermined the intent of USACE’s FY25 Civil Works strategy. Contract cancellations jeopardize forward-looking investments in climate resilience, environmental equity, ecosystem restoration, reduced interagency cooperation, and unpredictable policy shifts. Programs supporting disadvantaged communities, in particular, are vulnerable to disruption.

The Civil Works Budget: What’s Inside

USACE’s FY25 budget isn’t just about repairing infrastructure—it’s about reinventing it for the future. It includes:

- $79M in R&D to drive climate-resilient engineering

- $930M for inland waterway modernization, ensuring U.S. supply chains remain competitive

- $33M in O&M to enhance climate resilience

- $28M for zero-emission vehicle infrastructure

- $50M for mitigation of environmental and community impacts caused by legacy projects

- Other noteworthy projects include:

- South Florida Ecosystem Restoration (Everglades): $444M

- Howard A. Hanson Dam (WA): $500M

- Sault Ste. Marie Lock Replacement (MI): $264M

- Columbia River Fish Mitigation: $75.2M

So What?

Here are our takeaways.

Prioritize

Contracts backed by Congressional earmarks, state delegations, or aligned with influential infrastructure caucuses are less likely to be canceled by DOGE. Track Water Resources Development Act (WRDA) line items, FY26 appropriations bills, and NDAA developments for project-specific directives.

Focus

USACE’s civil works priorities—navigation, flood control, and dam safety—still receive bipartisan support. Rebalance your federal sales pipeline toward projects tied to navigation, critical water infrastructure, or Defense-funded military construction.

Avoid

Given the rollback of environmental justice and research programs by DOJ’s ENRD and DOGE, cooperative agreements and R&D-based grants may face high termination risk. Shift attention to competitively awarded contracts with firm funding and milestone-based deliverables.

Strengthen

USACE decisions are heavily decentralized. District offices still control much of the acquisition and procurement lifecycle. Invest in consistent outreach, local teaming, and district-specific capability statements—especially in regions like the Mississippi Valley, South Atlantic, and Great Lakes and Ohio River Divisions.

Invest

DOGE has cut many environmental programs but supports “efficiency upgrades” and physical infrastructure resilience that align with a cost-saving narrative. Position offerings around flood control system automation, structural rehabilitation, SCADA/cybersecurity upgrades, or power reliability, especially if they reduce long-term O&M costs.

5 Strategic Tips for Working with USACE

- Prioritize projects with strong Congressional support

- Focus on core mission areas with less political risks

- Avoid overreliance on cooperative agreements

- Strength district-level relationships

- Lean into infrastructure resilience and hardening

-

GSA 101: What Vendors Should Know About the General Services Administration

GSA 101

What Vendors Should Know About the General Services Administration

As the federal government enters a new phase of consolidation, cost management, and policy adjustment, the General Services Administration (GSA) is taking center stage. Its mission spans various responsibilities, from negotiating multi-billion-dollar acquisition contracts to overseeing the federal real estate portfolio. This makes GSA’s work influential across nearly every agency and, consequently, every American citizen.

The stark contrast between GSA’s collaboration efforts in 2024 and the shift towards siloed directives and complex, unfunded consolidation in 2025 has left GSA and its stakeholders confused and disoriented. With the rowdy release of a new Executive Order earlier this month, GSA’s course has been altered again, threatening significant ripple effects and long-term uncertainty for federal agencies and vendors. For now, we are left as onlookers, witnessing a potentially impactful case study – or an un pétard mouillé – on how the federal government adapts under significant and acute pressure.

This post provides a comprehensive overview of GSA’s foundational structure and services, offering a “roadmap” that clarifies how this agency supports the daily operations of federal government programs. We explore GSA’s organizational structure, its evolving roles, and the potential implications of disruptive federal policies and administrative changes for federal agencies, contractors, and the future of public service infrastructure.

Agency Overview

The Basics.

Established in 1949 by the Federal Property and Administrative Services Act, the GSA consolidated several federal agencies to centralize and streamline administrative services. Initially tasked with disposing of war surplus goods and managing federal records, GSA’s role has since expanded significantly.

Today, GSA supports more than one million federal civilian employees by managing real estate, acquisition services, technology infrastructure, and overall government operations. It operates through two primary services: the Public Buildings Service (PBS) and the Federal Acquisition Service (FAS), supported by 12 staff offices and 11 regional service offices.

GSA oversees the procurement of over $84 billion in goods and services annually. It also manages an extensive real estate portfolio, preserving over 480 historic buildings. Additionally, GSA implements federal digital strategies, supports climate initiatives, and aids presidential transitions. Recent strategic efforts include modernizing Land Ports of Entry, advancing shared digital services through 21st Century IDEA, and expanding innovative building technologies.

Federal Acquisition Service

Streamlining Procurement.

FAS, created in 2006 through the GSA Modernization Act, merged the Federal Supply Service and Federal Technology Service. Its mission is to simplify and modernize how the government buys goods and services. FAS operates across six main business areas: General Supplies and Services, Travel, Transportation and Logistics, Information Technology, Assisted Acquisition Services, and Technology Transformation Services.

FAS utilizes the federal government’s collective buying power to help agencies acquire goods and services efficiently. It manages the MAS program, which offers pre-negotiated contracts with commercial vendors, and oversees Governmentwide Acquisition Contracts (GWACs), the GSA SmartPay program, and emergency acquisition agreements. Through programs like the Federal Marketplace (FMP) Strategy, FAS is modernizing the acquisition experience for customers and suppliers by consolidating schedules, enhancing catalog management, and improving digital procurement tools.

FAS also supports innovative partnerships, such as working with the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) to transition Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) projects into contract-ready solutions. In addition, FAS spearheads efforts in green procurement, identity management (e.g., Login.gov), and technology modernization, including the shift from DUNS to UEI identifiers.

Public Buildings Service

Managing Federal Real Estate.

As the country’s largest public real estate and inventory organization, PBS serves as the landlord for the civilian federal government. It manages over 8,000 assets, totaling 370 million square feet of workspace across the U.S., and supports around 1.1 million federal employees. PBS also oversees 500 historic properties and more than $71 billion in owned value. It provides leadership and direction for architecture, engineering, urban development, sustainable design, historic preservation, construction, and project management.

PBS administers complex leasing and property disposal processes, utilizes innovative programs like the Automated Advanced Acquisition Program (AAAP), and supports the federal government’s net-zero carbon goals through initiatives like the Green Proving Ground. The service also supports art preservation, urban development, and inclusive employment through its Fine Arts and AbilityOne programs.

Recent PBS efforts focus on tackling deferred maintenance, consolidating the real estate portfolio, enabling green energy transitions, and improving leasing efficiency. PBS utilizes tools like Client Project Agreements (CPAs) and project lifecycle management frameworks to deliver effective property solutions. Major contract awards reflect priorities in modernization, building maintenance, energy procurement, and lease management.

Shakeups and Shifts

From Procurement Ecosystem to Procurement Epicenter.

The transition from GSA’s 2024 reorganization to the sweeping unfunded mandates of 2025 marks a significant shift in strategy, scale, and tone.

In 2024, GSA focused on realigning specific agencies and fostering customer-centric innovation. This included the introduction of APEX centers, modernization of procurement tools, and expansion of sustainability initiatives. These changes were collaborative, gradual, and driven by stakeholder engagement.

In contrast, 2025 brought rapid federal consolidation, sweeping Executive Orders, and aggressive cost-cutting measures that can only be compared to letting a toddler loose in a bank vault with scissors.

This abrupt change in pace and policy has created potential long-term repercussions—particularly for target agencies that may need to cede their procurement authority to GSA, and for vendors adapting to new expectations and reduced flexibility.

More importantly, this unrefined redirection could lead to reduced transparency, fewer entry points for small businesses in acquisitions, and an increased dependence on GSA-managed vehicles by government contractors.

2025 Rebrand

Slogan Pitch: “GSA’s Got It—Whether You Want It or Not”.

GSA will undergo another significant overhaul in 2025, driven by the Trump Administration’s policy direction.

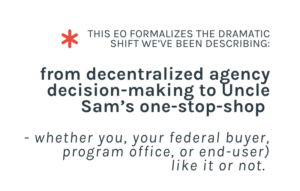

One of the most significant initiatives was announced on March 20, 2025, through an executive order titled “Eliminating Waste and Saving Taxpayer Dollars by Consolidating Procurement.” This order aims to reshape the federal procurement landscape by making the GSA the primary authority for domestic federal procurement of common goods and services. This effort builds on previous measures the Trump Administration took regarding the federal contracting marketplace, which has been characterized by bold claims and attention-grabbing headlines, such as GSA’s coordination of “the termination or economization of over 6,000 contracts across the federal government.”

At the same time, the Administration has enacted a 30-day freeze on the use of government-issued credit cards and initiated workforce reductions, with further cuts anticipated through the summer of 2025. A hiring freeze is also in effect until at least the end of the year. Recent policy changes have also impacted diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) practices, removing DEI considerations from government procurement evaluations.

“Rightsizing” MAS: Trimming the Fat—or the Access?

GSA is “rightsizing its Multiple Award Schedule (MAS) Program” by sunsetting contracts with low activity. Reports from yesterday indicate that GSA plans to remove up to 577 schedule holders over the next six months due to low sales, performance issues, or compliance concerns. Most of these companies have failed to meet their sales quotas in the past year or encountered performance or compliance problems. It’s important to note that this process of “removal” or “off-ramping” has been in place for some time under GSA’s Federal Supply Schedules (FSS) program, primarily governed by GSAM 552.238. This rule was established long before the current Administration and has been well-known: all FSS vendors must achieve $100,000 in sales within the first five years and $125,000 every five years thereafter. Additional modifications include the reduction in Special Item Numbers (SINs) where FAS plans to eliminate 31 SINs and modify several categories, including professional services and IT.

PBS Powers Down Its Climate Plans

Regarding PBS, the agency is divesting underutilized real estate to reduce maintenance costs—initial plans to sell hundreds of buildings have been scaled down to just eight sales. Meanwhile, sustainability programs such as electric vehicle (EV) charging station installations have been decommissioned. This includes approximately 8,000 charging plugs used for government and federal employees’ vehicles. Additionally, GSA plans to offload newly purchased EVs, aligning with the administration’s broader policy shifts away from previous sustainability initiatives.

Executive Order 14240: Legalizing Monopolies, Bundling, and Consolidation

The EO directing procurement consolidation under GSA is not unprecedented—it reactivates GSA’s foundational mandate under the 1949 Federal Property and Administrative Services Act to provide “an economical and efficient system” for federal procurement. The EO zeroes in on “common goods and services”, referencing the ten government-wide acquisition categories outlined by the Category Management Leadership Council (CMLC), a framework GSA already leads in six of.

The EO suggests that GSA may soon assume control of the remaining four categories, which are currently managed by the Department of Defense (DOD), the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and the Office of Personnel Management (OPM). Additionally, the GSA is expected to take over procurement responsibilities for the Department of Education (ED), the Small Business Administration (SBA), and the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).

If fully implemented, this would confirm that GSA is the central clearinghouse for nearly all domestically procured, non-mission-specific products and services governmentwide. This includes everything from software and office supplies to medical equipment and security services. This raises several important dynamics like:

- Category Management Becomes Control: What was once a flawed framework for collaboration could now be the legal rationale for full control. This reframes GSA’s role from a supportive shared services provider to a potential gatekeeper of federal commerce.

- More Guessing: The definition of “domestic” remains open to interpretation, which could create uncertainty in how this policy is executed—and which contracts fall under GSA’s future authority. Contractors and agencies will be left guessing how wide the net will be cast—and whether niche or specialized acquisitions might be caught in the dragnet.

- Operational Strain: GSA’s internal systems and acquisition workforce—already impacted by layoffs and a hiring freeze—is underprepared for such a surge in volume and responsibility.

Consolidation Without Capacity

GSA’s Growing Burden in a Shrinking Government.

The sweeping federal workforce reductions and restructuring across agencies are of profound significance to GSA, significantly altering the landscape of our operations.

The metrics to the right underscore the significant transformations within GSA, such as the consolidation of procurement functions, and the federal contracting landscape, including shifts in demand and changes in the structure of contract vehicles.

Operational Burden on GSA

As GSA assumes procurement responsibilities from agencies such as OPM, Education, SBA, and HUD, it inherits a large volume of work previously managed by thousands of acquisition professionals. This transition is straining GSA’s workforce, which must rapidly scale despite a federal hiring freeze. Compounding this pressure are government-wide layoffs draining available talent and limiting GSA’s ability to reassign staff or bring in new capacity.

Shrinking Federal Demand and Impact on Operations

Simultaneously, workforce reductions at customer agencies like CDC, HHS, and SBA are shrinking the federal demand base. Procurement cycles are slowing, acquisition pipelines through FAS are becoming less predictable, and PBS is experiencing a drop in demand for leased office space—all of which challenge GSA’s ability to plan, forecast, and deliver on mission support.

Loss of Institutional Knowledge

The rapid departure of experienced staff across GSA and the broader federal enterprise erodes institutional memory. This loss undermines smooth transitions, weakens compliance continuity, and makes managing large-scale policy or operational changes even more difficult.

Contractor and Industry Disruption

These shifts also affect the contractor ecosystem. Vendors—especially small businesses—are navigating fewer access points and changing agency priorities. Uncertain uncertainty and reduced engagement opportunities replace long-standing relationships and predictable procurement paths.

PBS Facility Challenges

PBS faces challenges as agencies shift toward hybrid work models. Space requirements are being reassessed, modernization strategies are under scrutiny, and divestment decisions are becoming more complex amid increased oversight and changing workplace needs.

In short, while GSA prepares to become the epicenter of federal procurement without any funding or congressional support thus far, it’s also operating in an environment where staffing shortages, increased responsibility, and shifting customer needs are blindly colliding.

GSA Workforce Reductions

- Overall GSA: Laid off ~600 employees in March 2025; more cuts expected. Targeting 50% overall spending reduction, including staff, space, and contracts.

- FAS: Eliminated the 18F/U.S. Digital Services program, cutting ~90 employees.

- PBS: Laid off ~600 in March; aiming for a 63% workforce cut. Cut ~40% of Region 9 staff (San Francisco, CA, NV, AZ, HI). Region 10 (Northwest/Alaska) issued RIF notices to 165 of 178 employees.

Est. Federal Workforce Reductions

- Defense: Plans to cut 5–8% of civilian staff—up to 61,000 jobs—including 5,400 probationary employees.

- Small Business: Plans to reduce its workforce by 43%, eliminating around 2,700 positions.

- Education: Laid off one-third of staff, about 1,300 employees.

- Environmental Protection: Trump expected 65% cuts (~11,000 jobs), but only ~170 impacted so far from shuttered environmental justice and diversity offices.

- Health and Human Services: Closing 6 of 10 OGC offices; ~200 of 300 regional staff to be laid off. NIH ordered to cut 3,400 jobs to 2019 staffing levels.

- Homeland Security: Issued RIFs for all staff in CRCL (~150), CIS Ombudsman (~40), and OIDO (~120); all on administrative leave.

- Labor: Plans to slash OFCCP workforce by 90%, cutting from ~500 to 50 employees and reducing offices from 54 to 4.

- Social Security: Plans to lay off 7,000 employees, per internal sources.

- Veterans Affairs: Targeting cuts to 2019 staffing levels—over 80,000 jobs. RIFs start this summer.

So What?

Here are our takeaways.

In a time filled with workforce reductions, operational shake-ups, and federal priorities that seem to change faster than a cat can chase a laser pointer, the GSA is entering one of the most significant evolutions in its history.

As the GSA tries to juggle internal cutbacks while balancing the tightrope of external growth, the long-term effects on trust, agility, and competition are still as clear as mud.

How the agency navigates this circus will influence the success of federal procurement and facilities management. Still, it will prove what’s possible when government organizations are asked to do more with less—like pulling off a three-ring circus act with half the performers and a new “under pressure” theme.

For those in the government contracting community, it’s time to stay as close to the GSA as a clingy toddler at a crowded playground. As procurement consolidates and operations shift faster than a squirrel on espresso, vendors should take a deep breath (or several) and reassess their contracting strategies.

Stay updated on Multiple Award Schedule (MAS) changes, evaluate pricing and compliance, and maybe use soothing, meditative tones when engaging with GSA contracting officers. Picture waterfalls and gentle breezes—remember, calming vibes only!

-

Entry Points into Federal Contracting

Breaking Down GWACs, BICs, and MACs

It’s no secret that the GovCon ecosystem uses a lot of acronyms. For small businesses or organizations that are just starting out in GovCon, it’s important to understand the many terms used, like GWACs, BICs, and MACs, to get on the same level as competitors. We at The Pulse have organized a guide to understanding these federal contract types and how your organization can best use them.

GWACs

Government Wide Acquisition Contracts

A task-order or delivery-order contract for information technology products and services established by one agency for government wide use. GWACs are governed by the Clinger-Cohen Act and provide inter-agency access (inter-agency: between two or more agencies).BICs

Best-in-Class Contracts

Government contract vehicles that are deemed the highest performing contracts by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) because they defined “key criteria” for management maturity and data sharing. BICs are the primary tool critical to the operation of Category Management (CM). BICs are not limited to information technology vehicles.MACs

Multi-Agency Contracts

An inter-agency contract that is governed by the 1932 Economy Act. MACs are also a task-order or delivery-order contract, but they are authorized to acquire a variety of supplies and services. However, GSA MACs are not subject to the Economy Act. These are not to be confused with Multiple-Award Contracts.IDIQs

Intra-Agency Indefinite Delivery/Indefinite Quantity Contracts

An intra-agency (intra-agency: within the same agency) contract allows an agency to purchase an undefined quantity/delivery over a set period while being restricted within the awarding agency. The government uses these contracts when it cannot predetermine, above a specified minimum, the precise quantities of supplies or services that it will require during the Period of Performance.History of GWACs, BICs, and MACs

So, which of these came first? Time for a quick history lesson.

Timeline:

1932: The Economy Act creates MACs.

1996: The Clinger-Cohen Act creates GWACs.

2005: GWACs are categorized as high-risk federal functions.

2012: Improving Acquisition Through Strategic Sourcing Memo.In 2014, OFPP under OMB, announced its Category Management initiative (an evolution of Federal Strategic Sourcing Initiative [FSSI]) to further streamline and manage entire categories of spending across the government to act more like a single enterprise.

Both initiatives were established to accomplish the same goals of achieving significant savings, decreasing administrative redundancies, and improving business intelligence.These goals were all meant to occur while also meeting or exceeding small business and sustainability goals. Category Management is meant to succeed where FSSI failed – in the implementation, utilization, and adoption of GWACs and MACs. Under Category Management, GWACs and MACs serve as the motivating force through the utilization of BIC solutions across a variety of federal agencies. BICs allow Category Management to achieve its objective to buy “as one” by consolidating all requirements into a limited number of preferred government-wide contracts.

How to Identify BICs

The most important thing to know here is that Google doesn’t help. There is a list from 2019, distributed by the Department of Energy, that shows BICs by category. This document states, “Always check the BIC Research Tool and Solutions Finder in the Acquisition Gateway for the latest BICs.” Online, using the Acquisition Gateway website, choose the Solution Finder, then filter using the “Govwide Initiative” option with “Best in Class” selected.

For those who are already familiar with BICs, it’s important to note that not every GWAC, BIC, or MAC started out as a BIC… Including:

Navy: SeaPort-NxG

GSA: Professional Services Schedule (PSS), Polaris

VA: Transformation Twenty-One Total Technology Next Generation (T4NG)

DOJ: Information Technology Support Services (ITSS-5)Impact Across the Ecosystem

Since 2016, there has been a shift to consolidate federal procurement pathways under the Category Management initiative in the federal government.

Cost Savings: As of 2020, OMB has reported the federal government has saved $27.3 billion in 3 years.

Increased Requirements Bundling: Since the process focuses more on the contracting process, the approach to defining requirements has further broken down.Less Access: BICs minimize channels for acquisition and reduce lanes where contractors can supply services and products. In the end, it’s very likely that the same vendors will be on GSA Polaris, as well as on HHS CIO-SP4, and most of them also on GSA 8(a) STARS III – with no differentiation. As a result, the government does not gain access to a wide range of solutions and services from the actual federal marketplace.

Impact Across the Ecosystem

Since 2016, there has been a shift to consolidate federal procurement pathways under the Category Management initiative in the federal government.

Cost Savings: As of 2020, OMB has reported the federal government has saved $27.3 billion in 3 years.

Increased Requirements Bundling: Since the process focuses more on the contracting process, the approach to defining requirements has further broken down.Less Access: BICs minimize channels for acquisition and reduce lanes where contractors can supply services and products. In the end, it’s very likely that the same vendors will be on GSA Polaris, as well as on HHS CIO-SP4, and most of them also on GSA 8(a) STARS III – with no differentiation. As a result, the government does not gain access to a wide range of solutions and services from the actual federal marketplace.

In the Market/Industry:

Fewer and fewer vendors have been successful in accessing, competing, and remaining in the market since the shift to BICs. There have been consequences of this competition downsizing.

- Competitors buying competitors or buying into a sector to increase revenue

- Consolidation of firms with <1,000 employees through private equity

- Vendors diversifying into commercial or foreign markets

- Vendors decreased ability to support and grow an internal workforce required to compete in the market

For Government Contractors:

- Less Access: The move to BICS has resulted in less access and transparency into government procurement activity and opportunities.

- Biggest in Class or Best in Class?: Teaming, JV, and Mentor-Protege have become vitally important for government contractors. To receive a contract award on one of these GWACs or MACs, a Prime contractor must either be one of the biggest players in the market or team up with enough companies to turn into one.

- Increased Bottom Line: Mixed messages and the usage of these procurement vehicles meant to simplify acquisition have proven hefty to vendors’ Bid & Proposal (B&P) bottom lines. Vendors spend tens of thousands of dollars trying to secure a place on specific GWAC, MAC, or BIC contracts because they know their survival in this marketplace could depend on it.

- Small Businesses, Who?: There has been a continuous decline in small business vendor utilization across Best-In-Class (BIC) vehicles since FY19.

How to Capitalize on GWACs, MACs, and BICs

Now that you’re armed with the knowledge of what these contract types are, their history and effects, let’s look at key ways to use them to your business’s advantage

Understand the difference.

- Be selective in which ones you pursue based on on-ramping periods, scope & services, and your strategic goals for the future.

- Remember that you don’t need every hot contract that hits the streets. Do what’s best for your business and pursue what’s right for your team.

Don’t let them sit dusty on your shelf.

- BICs don’t make you money unless you leverage them.

- Have a task order response cell (TORC) in place or else have a “participation” trophy.

Push new work to the ones you hold.

- Know your buyers and customers, and who uses what.

- Make these vehicles part of your sales effort and increase visibility through targeted marketing.

Knowing the differences and nuances of GWACs, MACs, and BICs will help you navigate the federal market successfully. Despite the federal shift to BICs that has led to decreased competition and other negative effects for contractors in recent years, it is still possible to successfully pursue and leverage these contracts.